The Jesus Archive recently visited Bryan Walsh, director of the Shroud of Turin Center outside Richmond, Va., where he lectures on the Shroud and maintains a laboratory. This summer, he has been investigating how the 1988 radiocarbon dating, which indicated a Shroud origin between 1260 and 1390 C.E., could have erred. He provided a detailed exposition of his findings at the Shroud of Turin Conference in Dallas in late October.

Jesus Archive: Radiocarbon dating proved to the satisfaction of almost everyone in the scientific community that the Shroud of Turin originated in the Middle Ages. What grounds would reasonable people have to question the results of that test?

Bryan Walsh: Radiocarbon dating is only one of the tools used to date an artifact. If you look at radiocarbon tests in archaeological datings over the past 20 years, you’ll find that about one percent of them are discarded. Archaeologists use stratigraphy, paleography, and many other methods to establish age. They use radiocarbon dating to narrow down or confirm the date of an object, but if the radiocarbon result is an outlier – if they’re anomalous – they will chuck it out. Radiocarbon dating is not infallible. For example, ten to fifteen years ago, radiocarbon tests showed a number of seashells to be tens of thousands of years old, yet they came from clams that had died only recently. It turns out that the radiocarbon reservoir that these clams grew up in was depleted in carbon-14, which caused them to be dated older than they actually were. In the case of the Shroud, there is evidence that the sample used for the radiocarbon dating was heavily contaminated, and the nature of this contamination may have affected the date derived.

JA: Contaminated? How?

BW: In 1532, fire broke out in the Sainte Chapelle in Chambery, France, where the Shroud was stored in a silver reliquary. You had a linen cloth contained in a silver box lined with wood, which was exposed to temperatures reaching 850 degrees Celsius. The way the box was kept in the wall – fitting in a slot between big blocks of stone — created a steep thermal gradient ranging from 200 degrees Celsius to 850 degrees Celsius. The wood inside the reliquary acted as a partial insulator, so the Shroud cloth was exposed to a very low oxygen environment at about 200 degrees Celsius, causing it to become slightly yellowed. But the wood was exposed to much higher temperatures. The wood went through a three-step degradation process. Above 120 degrees, it gave off water in the form of steam. Above 200 degrees, the wood went through a process of torrification, emitting carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, water vapor and even a little methane. The wood on the top front portion of the box, nearest where the Shroud sample was taken from, got to more than 350 degrees Celsius. At this range, depolymerization occurs. The wood broke down and gave off all sorts of chemicals: acetyls, furfurals, aldehydes, ketones and other beasts from the carbon zoo.

JA: Bryan, I’m not a chemist. Do you mean that the wood began to burn and give off smoke?

BA: No, the inside of the reliquary was a low-oxygen environment, so combustion didn’t occur until the silver of the reliquary melted and droplets of silver fell onto the Shroud linen. But chemical changes were taking place; chemicals were being emitted, both by the wood and the Shroud linen. The pyrolytic chemical mix was exposed to the cloth for at least two hours prior to the silver melting. When the people who owned the chapel got the reliquary out of the space, they poured a bucket of water on it. The water comes from the city of Chambery in the French Alps, between two limestone mountain ranges. It’s high in calcium carbonate, sodium carbonate, aluminum sulfate, and all sorts of salts. That water was poured on the Shroud. It became superheated. It turns out that when cellulose – which the linen Shroud is composed of — is exposed to certain metallic salts at elevated temperatures, the salts act as a catalyst. As a result, the cellulose reacts with chemical products in the environment that it wouldn’t otherwise easily react with.

JA: So, it was a real chemical soup inside the reliquary. The combination of heat and salts might have incorporated carbon-14 from the scorched wood into the cellulose structure of the Shroud.

BA: Exactly. In 1996, Dr. Al Adler did some FTIR tests[1] on some threads taken from each side of the Shroud radiocarbon sample site. He found that both sets of threads were high in calcium, potassium, sodium, aluminum and magnesium salts. The salts are deposited in a gradient; the salt concentration declines as you move away from the edge of the seam on the Shroud, as if the cloth were bathed in a salt-rich solution. That conforms to my statistical analysis of data from the radiocarbon dating published in 1999 showing a similar gradient in radiocarbon measurements. Here at the Shroud of Turin Center, we’ve concluded that the salts embedded in the Shroud linen were most likely from the Chambery water source, and we’re working now on trying to understand the chain of chemical reactions that caused the carbon dating to be skewed.

JA: What makes you different from the hundreds of “shroudies” out there who will grasp at any wild theory to justify their faith in the authenticity of the Shroud?

BW: I don’t have a “faith” – a belief in things unseen — in the authenticity in the Shroud, but a desire to evaluate all the information available about it. I’ve done a lot of research personally on all of these theories, accepted some, discarded others, then looked at the science behind them. I found a substantial body of scientific evidence by scientists of good repute that point to the authenticity of the cloth. Most people – shroudies and skeptics alike — have not done that kind of research. They have not looked at the journals.

JA: If you’re right, what are the implications for Shroud research?

BW: My hope is to re-establish the Shroud as a useful and viable research field so that we can get more researchers interested in looking at its physics, history and chemistry and explain its many unique features.

JA: How do you think the image on the Shroud was created?

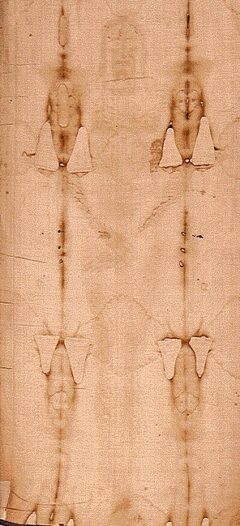

BW: My personal belief is that the Shroud is authentic, not a Medieval forgery. The Shroud image is unique. First, it acts as a photonegative showing the image of a crucified man on the Shroud. Second, body mapping – measuring the distance from the cloth to the body – allows you to create an accurate 3-D relief of the image. And Third, the image is very superficial. The oxidized/dehydrated fibers forming the image lie only at the very top of the linen fiber bundles. It appears that a projection of a columnated field of short-wave radiation, vertically oriented towards the axis of gravity, dehydrated and oxidized the surfaces of the Shroud cellulose fibers.

Another feature obvious on the visible light images of the Shroud is that the hands appear to be elongated. It turns out that you are looking at the bones of a human hand under the skin. You get similar kinds of imaging characteristics around the teeth and the eye sockets, indicating that whatever occurred acted like a reverse dental x-ray. It was as if the x-ray machine was placed inside the body and pointing out, and the image was left on the cloth that surrounded the radiating body. The image appears to have been made when the cloth was relatively flat, causing a misregistration of the bloodstain images in some places. Under the bloodstains there are no other image characteristics – just plain linen. That implies that the radiative image occurred when the body was no longer there, after the bloodstains had been placed on the cloth by contact. You get the flattening cloth falling through the space the body had occupied, leaving an oxidation effect on the linen. In layman’s terms, a burst of radiative energy originated from within the body, as the body disappeared, registering on the Shroud as it collapsed through the space formerly occupied by the body.

JA: Many New Testament scholars question the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ burial in the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea and the subsequent discovery of the empty tomb. The narratives differ on essential points. Clearly, a significant amount of literary invention was going on. How do you reconstruct the events surrounding the discovery of the empty tomb and the burial linens?

BW: I don’t reconstruct them. I take the Gospel accounts as a set of observations that should conform to Jewish burial practices of the time.

JA: The Gospel of John tells us that Peter “went into the sepulcher, and seeth the linen clothes lie, and the napkin, that was about his head, not lying with the linen clothes, but wrapped together in a place by itself.” (John 20:6-7) If Jesus were buried with a cloth around his head – a practice confirmed in John 11:44 in regard to Lazarus – how, according to your theory, did an image appear on the main burial linen, the Shroud? And how did the napkin wind up “wrapped together in a place by itself”?

BW: Our research indicates that the Jews buried a crucified man like Jesus by placing a cloth around his head while still on the cross to capture any “mingled blood” and then took the body down from the cross. They put the body of the man on a separate linen sheet and carried it to the tomb. They removed everything on his body, including the cloth over his head, wrapped him in a clean burial shroud, and placed the cloth that was over his head – and anything else bearing blood – at his feet. A head-cover cloth like this – the Sudarium of Oviedo – has been known to exist at least since the 6th century and resides in Spain today. It’s been described historically as the cloth used to cover Jesus’ face, and it’s embedded with blood and bodily fluids, but no image. The blood type, AB, conforms to that of the Shroud. The Sudarium may be the napkin referred to in the Gospels.

JA: Let’s accept your theory for purposes of argument. Trace the early history of the Shroud. Who took possession of it – Peter? The Beloved Disciple?

BW: That is a matter of intense investigation and a lot of speculation. There are several references pointing to Peter having the cloth that was over Jesus’ head. Ishodad of Merv, the bishop of the town of Merv in Turkmenistan in the 9th century, writes in his Commentaries on the Gospels that Peter, after Jesus arose from the dead, used the cloth that was over Jesus’ head as part of the ceremony where he’d consecrate priests and deacons, and also used it to heal people. That makes some sense. Go back to the Old Testament: The high priest Aaron wore a linen turban bigger than anyone else’s. It appears that Peter used the Shroud as a turban, or a mitre – he wore it on his head.

Another partial confirmation comes from a reference in the “Life of Saint Nino,” who came to Jerusalem with her parents from Cappadocia. She wanted to track down the tunic of Jesus and in her travels was captured and taken to what is now the country of Georgia. She relates of having heard stories while in Jerusalem of Pilate’s wife taking the burial cloth of Jesus with her up to her house in Pontus, near the Black Sea. In this recounting, Saint Luke took it from her and hid it, and nobody knows where. There’s another tradition that St. Luke preached in Bithynia and in Achaia, which may give some indication of where he might have hid the burial cloth. The problem with these stories is that you can’t get collaboration. But you can’t dismiss them as pure legend and bunk either. There isn’t enough data to reach a firm conclusion.

The possibility of St. Luke possessing the Shroud is interesting, by the way, because he is purported to be an artist, among other things in Christian tradition. He purportedly painted images of Jesus and his mother Mary. His reported preaching in Bithynia is intriguing because there are many Byzantine reports from the mix-6th Century of a cloth bearing an image of Jesus showing up in Kamuliana in Cappadocia. The connection between St. Luke and the images of Jesus is intriguing, and more research needs to be done.

JA: So, you’ve got these disciples claiming that Jesus had arisen from the dead. They encounter skepticism in their own ranks – doubting Thomas being the most obvious example. They encounter skepticism among their fellow Jews, not to mention the Temple authorities. If they possess this extraordinary piece of evidence – a burial shroud miraculously showing the image of Jesus – why do they not present it as proof of their claims? Why are the sources silent?

BW: There are several hypotheses. The Christians were persecuted in and around Judea. They were attracting more Jewish converts. The Jewish powers that be resented them. They had to hide whatever resources they had from possible destruction, and may have taken them out of the country for safety reasons. With the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D., the Christians had to flee if they could. They went up to Pella in the Decapolis, taking their possessions. Some of them may have gone from there to Antioch.

After the Jewish authorities persecuted the Christians, the Romans began persecuting them – for “eating flesh,” celebrating the Eucharist. You don’t find many references to the Eucharist during that time. There’s a reason: The Christians were keeping it secret. We think the Shroud, like the Eucharist, may have been an important part of the Christian faith in the early days and was thus kept secret.

But there’s another possibility. If the image was created by radiation, and if the radiation was of a certain kind – protons or soft x-rays – there may have been no image on the Shroud for the first 100 or 200 years. The dehydrated and oxidized fibrils don’t turn yellow for some time. You need a process called carboxylation to occur. It’s possible that the early Christians kept the Shroud as a reminder of Jesus, even though they didn’t see the image for a long time. That might help explain why the earliest representations of Jesus conformed to the Hellenistic stereotype of a beardless youth, but some time around the 6th century, Byzantine iconography suddenly begins showing him as a bearded man of Judaic appearance. There are many theories but no conclusive evidence. A lot of research remains to be done.

JA: How did the Shroud end up in the hands of a French nobleman in the 1300s?

BW: The Shroud may have been in Constantinople for some time. In 1204, just before the Fourth Crusade, a French knight, Robert de Clari, describes seeing a cloth with the image of Jesus displayed every Friday rising up straight so that anyone seeing it could see Jesus’ features. John Jackson, director of the Turin Shroud Center in Colorado Springs, wrote a paper two years ago showing that the fold marks and tack marks and stains found on the Turin Shroud match a folding pattern that would have been necessary to show the image of Jesus described by de Clari, when held up straight, from the top of his head to his folded hands. The Shroud of Turin, displayed in this way, probably was the basis for the Byzantine artistic tradition called the “Extreme Humility” icon tradition. In 1204, you had the Fourth Crusade, in which the crusaders sacked Constantinople. In 1205, there’s a letter to the Pope saying that the Shroud was in Athens and that the French had it. Geoffrey de Charny’s ancestors apparently took control of the Shroud in Athens, then took it to France. All the pieces haven’t been put together yet, but I think that’s how it will settle out.

JA: Which comes first for you: Your faith in the Shroud or your dedication to the scientific method? Let’s say someone conducted another radiocarbon dating of the Shroud with the proper controls and confirmed a Medieval origin. Would you accept the findings?

BW: I couldn’t ignore them. The problem with the question you pose is that it ignores all the other data. At the end of the day, I don’t think your scenario is going to happen.

JA: What keeps you going? Is it the intellectual excitement of solving a great mystery?

BW: If in fact the Shroud bears the image of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, it is probably the most important artifact on the face of the earth. As you dig into it, you find all this history that’s fascinating. The science is fascinating. It’s fascinating from any number of angles – that’s what keeps me going.

[1] FTIR – Fourier Transform InfraRed spectroscopy, a non-intrusive method of extracting precise chemical information from small samples using infrared light.